Like so many things that eventually go wrong in American history, the story of the so-called “Indian Romance” can, I think, be traced back to a white person who thought they had good intentions. In 1881, an east coast social crusader named Helen Hunt Jackson wrote a non-fiction book called A Century of Dishonor, detailing the previous 100 years of federal mistreatment of Indigenous Peoples. Jackson sent a copy to every member of Congress in an attempt to persuade them to treat Indigenous Peoples more fairly. Despite Jackson’s best efforts, the book failed to move public policy. Instead, she felt it was time to turn to fiction in an attempt to win over hearts and minds.

In 1884, Jackson published Ramona, a story about a woman of mixed Scottish-Native American ancestry and the mistreatment she faced at the hands of missionaries and settlers in California. Underpinning the story is a criticism of federal laws that made it easy for settlers to seize lands from indigenous people, but it was the Spanish missions and the doomed love of Ramona and sheepherder Alessandro that drew most of the attention. The book was massively popular upon its publication, and while less well-known now, has never been out of print.

Helen Hunt Jackson died in 1885, just a year after the book was published. As such, she never got to see the two major unintended consequences of Ramona. The first was the passage of the Dawes Act in 1887, which some credit to Jackson’s work, and broke up the communal lands of Native Americans and forced them to accept American citizenship. While ostensibly designed to avoid the land seizures highlighted by Jackson’s book, it was immensely destructive to Native culture and societies. At the same time, Jackson’s romantic portrayals of Spanish missions and California life became a promotional tool for tourism and real estate development in the state. An open-air play based on the book, called the Ramona Pageant, began in 1923 and continues annually to this day. The name Ramona appeared everywhere in California as a tribute to Jackson’s heroine, from schools to highways.

Ramona’s portrayal of settlers and “noble savages” would became a major pillar of the Western genre in American popular culture. Versions of the love story between Ramona and Alessandro, typically between a white settler and a Native American appeared in books and films for decades. Ramona itself has been made into a film five times, including a 1910 D.W. Griffith adaptation that featured Mary Pickford in the title role.

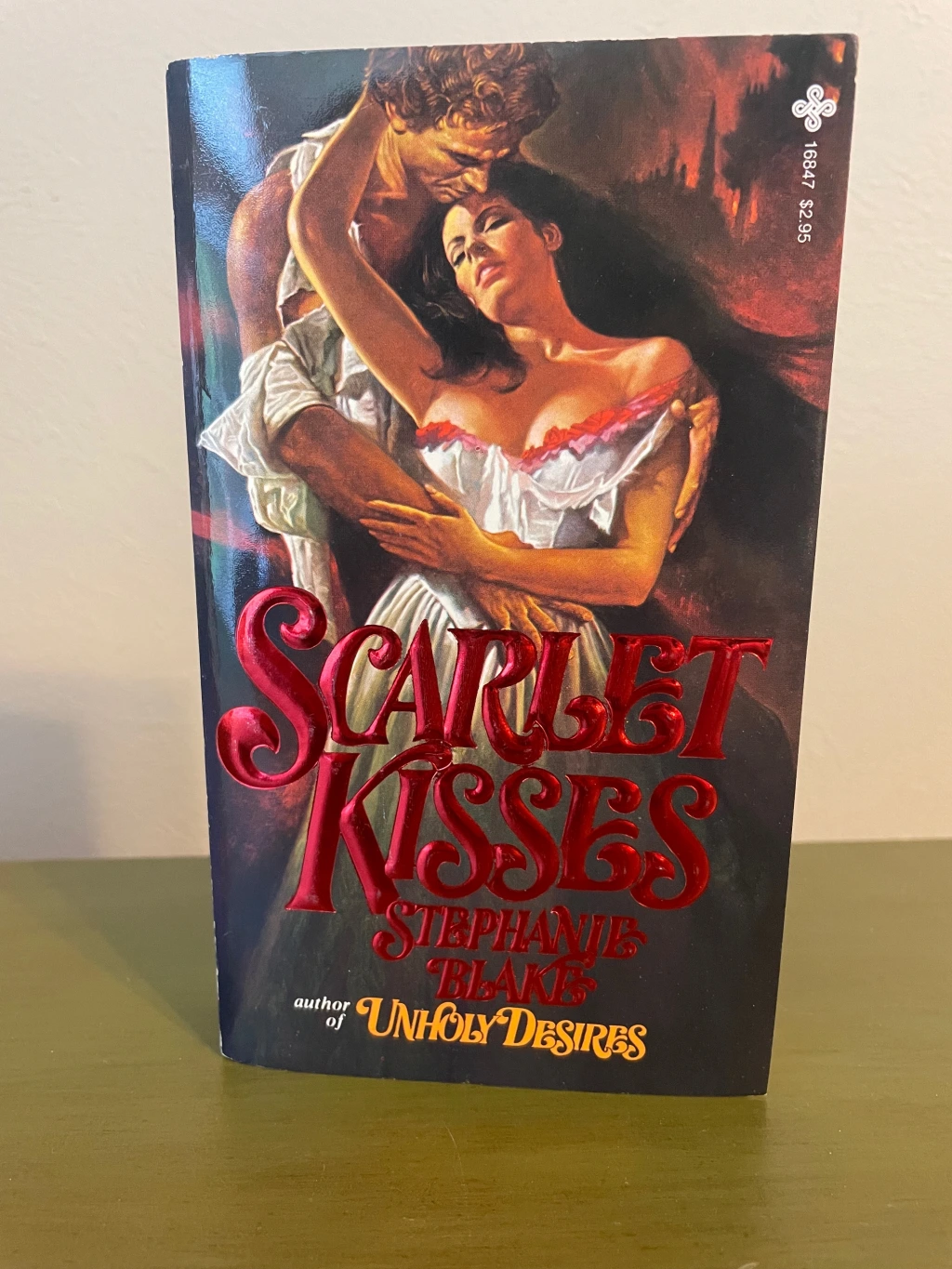

With the growth of historical romance in the 1970s and early 1980s, it seemed inevitable that Western stories would become part of the genre. Nakoa’s Woman by Gayle Rogers, published around the same time as Kathleen Woodiwiss’s The Flame and the Flower in 1972, features the cover blurb “A fierce Indian warrior, a beautiful white captive- an enthralling love story”. Variations on this setup would become the norm for the so-called “Indian Romance”, which really exploded in 1981 with the publication of Janelle Taylor’s Savage Ecstasy. Taylor and her fellow Zebra/Kensington author Cassie Edwards would go on to be responsible for more than 100 “Indian Romances”, most of which feature “Savage” or some variation in the title. And they were not alone. The subgenre was massively popular, so much so that from 1984-1993, Romantic Times gave awards for the “Best Indian Romance”.

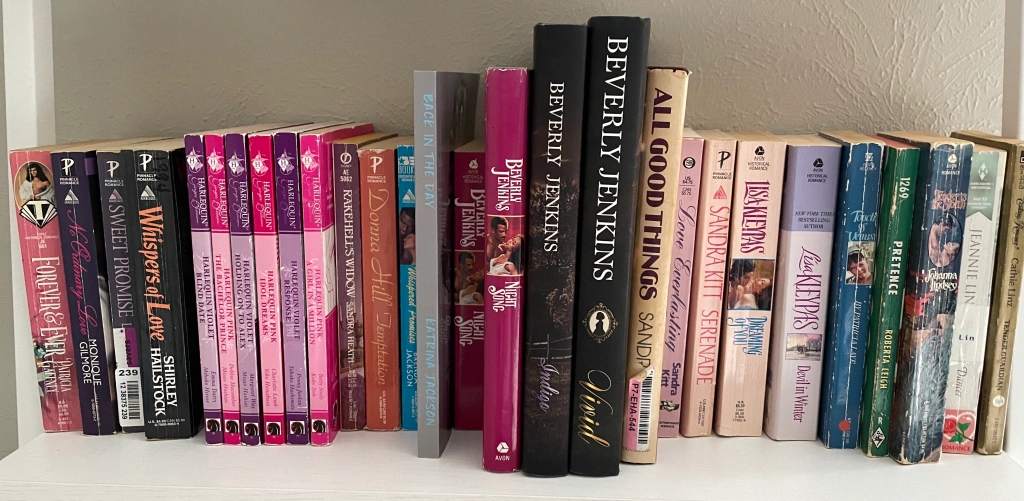

Images from Goodreads

Written almost entirely by white women who pride themselves on the “accuracy” of their research, the books rely on the same noble savage tropes used by Helen Hunt Jackson, with Native Americans portrayed as either fierce warriors or submissive (but strong) women. Their love stories are never between Native Americans, but always involve a white person (or “half breed”) as the hero or heroine. The authors pride themselves on research into ceremonies and dress, but at the same time portray love stories that rarely if ever happened in the time period they are writing about.

The stereotypes portrayed in the so-called “Indian Romance”, however well-intentioned they may have been in Helen Hunt Jackson’s day, are flat-out racist. They reinforce notions of Native Americans as savages who only existed in the past, when they are right here with us, right now. Native men are frequently portrayed as supposedly noble, but also as violent rapists who need the love of a white woman to tame them. The continual use of “Savage” in the titles piles on another layer of insult disguised as a compliment.

It’s really important to know that these books have not disappeared. They are not just some relic of the past. Kensington Publishing still sells the books of Janelle Taylor and Cassie Edwards, which is shocking considering that the company was on the vanguard of publishing the stories of Black and Latinx love. A review of Goodreads will show that people are still reading these old books, and giving them 5 stars. And inspirational publishers like Bethany House have clearly gotten in on this as well, with Kate Witemeyer’s At Love’s Command landing an RWA award this past weekend. Witemeyer’s book doesn’t strictly match the relationships of the books of Edwards and Taylor, with both protagonists being white, but the fact that the plot revolves around a revisionist (and white supremacist) history of the Wounded Knee Massacre and the hero’s involvement in killing Lakota peoples, I see no issues with lumping them together.

I’ve found little organized resistance to the racist tropes and narratives of “Indian Romance” outside of the most recent outrage, and there’s a lot to unpack in why that is that I’m not going to get into today. Let’s suffice it to say that I think the reason we see these books survive today is because few readers, authors, and publishers were interested in standing up against them when they were published, so they continued to stay on shelves for new readers to find. I hope that the renewed awareness brought about by this year’s RWA awards can start to change that.

In all of this, Native American voices have rarely been heard in romance. That is slowly changing. Pamela Sanderson’s Crooked Rock series and Robin Covington’s Redhawk Reunion series are just two examples of Native authors writing contemporary stories of indigenous people finding love without the harmful stereotypes of romance’s past. Let’s hope that more are on the horizon.

Note: I’ve chosen not to link to the offensive titles that I mention above. While I’m happy to link to other works that I discuss on my blog, most of the works I mention here deserve no such consideration. They are readily available, I assure you.

Leave a reply to azteclady Cancel reply