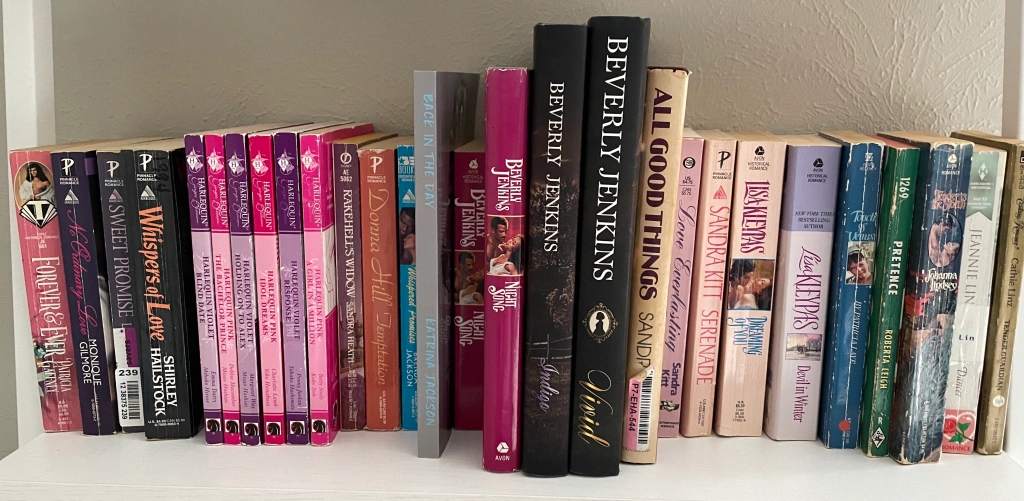

While I like to use Black History Month as an opportunity to share stories of Black love, there’s another aspect of the romance industry that I think is worth highlighting to give context to the experience of Black authors in the genre.

As the 1980s began, shorter “category” romances served as the main vehicle for new authors to enter the genre. Publishers like Dell (Candlelight), Harlequin, Silhouette and Bantam (Loveswept) published dozens of books a month between them, creating a huge demand for new authors. Despite this need for content, those publishers would only released a handful of romances featuring Black characters even until the mid-1990s. The overwhelming whiteness of the genre only lifted when Black editors like Vivian Stephens and Veronica Mixon were in charge. For many aspiring Black romance authors, the industry’s lack of interest in Black stories and Black readers meant they frequently had a stark choice- you could write a story of Black love, or you could sell a manuscript.

The four Black authors I highlight here are examples of those who wrote white stories within the genre’s white supremacist structure before finding ways to tell stories of Black love. It’s worth noting that there may have been many other Black writers who took this path, we just don’t know for sure who they were.

Barbara Stephens

The sister of famed editor Vivian Stephens, Barbara Stephens was a founding board member of the Romance Writers of America when the organization was formed in late 1980. In 1981, using the pen name Barbara South, she published Wayward Lover with Silhouette. That novel, like all Silhouette Romances to that point, featured white main characters. In 1984, Stephens published A Toast To Love with Doubleday’s Starlight Romance line. It was the line’s first book to feature Black main characters. She published one more romance, 1991’s Midnight Waltz with Black owned independent publisher Odyssey Books.

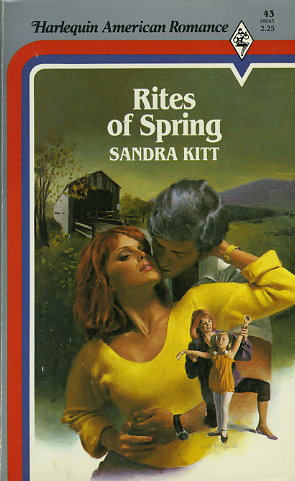

Sandra Kitt

Sandra Kitt began her publishing career with Harlequin in 1984 as one of the authors signed by Vivian Stephens during the early days of the Harlequin American line. In 1985, her second Harlequin American title, Adam and Eva, became the publisher’s first ever romance to feature Black main characters. Of the eight titles Kitt published for Harlequin between 1984 and 1991, seven of them featured white couples. Kitt has said that Harlequin was simply not interested in her story ideas that included Black characters. Since leaving Harlequin, Kitt has been publishing the Black and interracial romances and women’s fiction she wanted to see, first with Odyssey Books, then Signet, and in 1994 she was one of the launch authors for Kensington’s Arabesque line. She now writes for Sourcebooks Casablanca.

Chassie West

Perhaps best known today for her Leigh Ann Warren series of mystery novels, Chassie West wrote a number of YA mysteries and romance during the 1980s for series such as Scholastic’s Micro Adventures and the Nancy Drew Files, as well as Silhouette’s YA First Love romance line. She adopted the pen name Tracy West for three First Love romances featuring Black main characters beginning with 1982’s Lesson in Love, and the pen name Joyce McGill for several romances with white main characters. In the early 1990s, she moved over to Silhouette’s Intimate Moments to write a number of adult romantic suspense books under her Joyce McGill pen name. In 1992, her Intimate Moments book Unforgivable became Silhouette’s first adult romance to feature Black main characters. Unforgivable was her last book for Harlequin, and in 1994 she switched to mystery permanently, publishing Sunrise, her first Leigh Ann Warren mystery.

Eva Rutland

Even for an era when many romance authors began writing later in life, Eva Rutland was a late bloomer. To Love Them All, her first Harlequin Romance title, was published in 1988 shortly after her 71st birthday. Rutland wrote 18 titles in all for Harlequin, including 1989’s Matched Pair, the launch title for Harlequin’s return to Regency romance. All but one of Eva’s Harlequin books revolved around white characters. She related in a later interview that a friend had warned her Harlequin wouldn’t buy any books with Black characters, so she stuck with what had worked for her. It wasn’t until 1996 that Rutland would write a story with Black characters, the novella Guess What’s Cooking for Sisters, the first of two collaborations with Sandra Kitt and Anita Richmond Bunkley published by Signet. Her final book for Harlequin- 2005’s Heart and Soul -was Rutland’s only Harlequin title to feature a Black female main character, as part of an interracial couple. Eva Rutland died in 2012 at the age of 95.

These four women and others like them took on the prejudices of the romance genre head on, showing that not only did Black women read romance in greater numbers than publishers thought, but also that Black authors could be popular and successful no matter the obstacles publishing put in their way.

Leave a comment